Ein hochauflösendes Bild der Erde, aufgenommen vom japanischen Mondorbiter Kaguya im November 2007. Bildnachweis: JAXA/NHK

Eine neue Ära der Monderkundung bahnt sich an, mit Dutzenden von Mondmissionen, die für das nächste Jahrzehnt geplant sind. Europa steht hier an vorderster Front und trägt zum Bau der Gateway-Mondstation und des Orion-Raumfahrzeugs bei – die Menschen zu unserem natürlichen Satelliten zurückbringen sollen – sowie zur Entwicklung des großen logistischen Mondlanders, bekannt als Argonaut. Da Dutzende von Missionen auf und um den Mond operieren und unabhängig von der Erde miteinander kommunizieren und ihre Standorte festlegen müssen, wird diese neue Ära ihre eigene Zeit benötigen.

Dementsprechend begannen Weltraumorganisationen darüber nachzudenken, wie man die Zeit auf dem Mond halten könnte. Die Diskussion, die mit einem Treffen im Technologiezentrum ESTEC der Europäischen Weltraumorganisation in den Niederlanden im vergangenen November begann, ist Teil einer größeren Anstrengung, sich auf etwas Gemeinsames zu einigen.Luna-NetzArchitektur für Mondnavigation und Kommunikationsdienste.

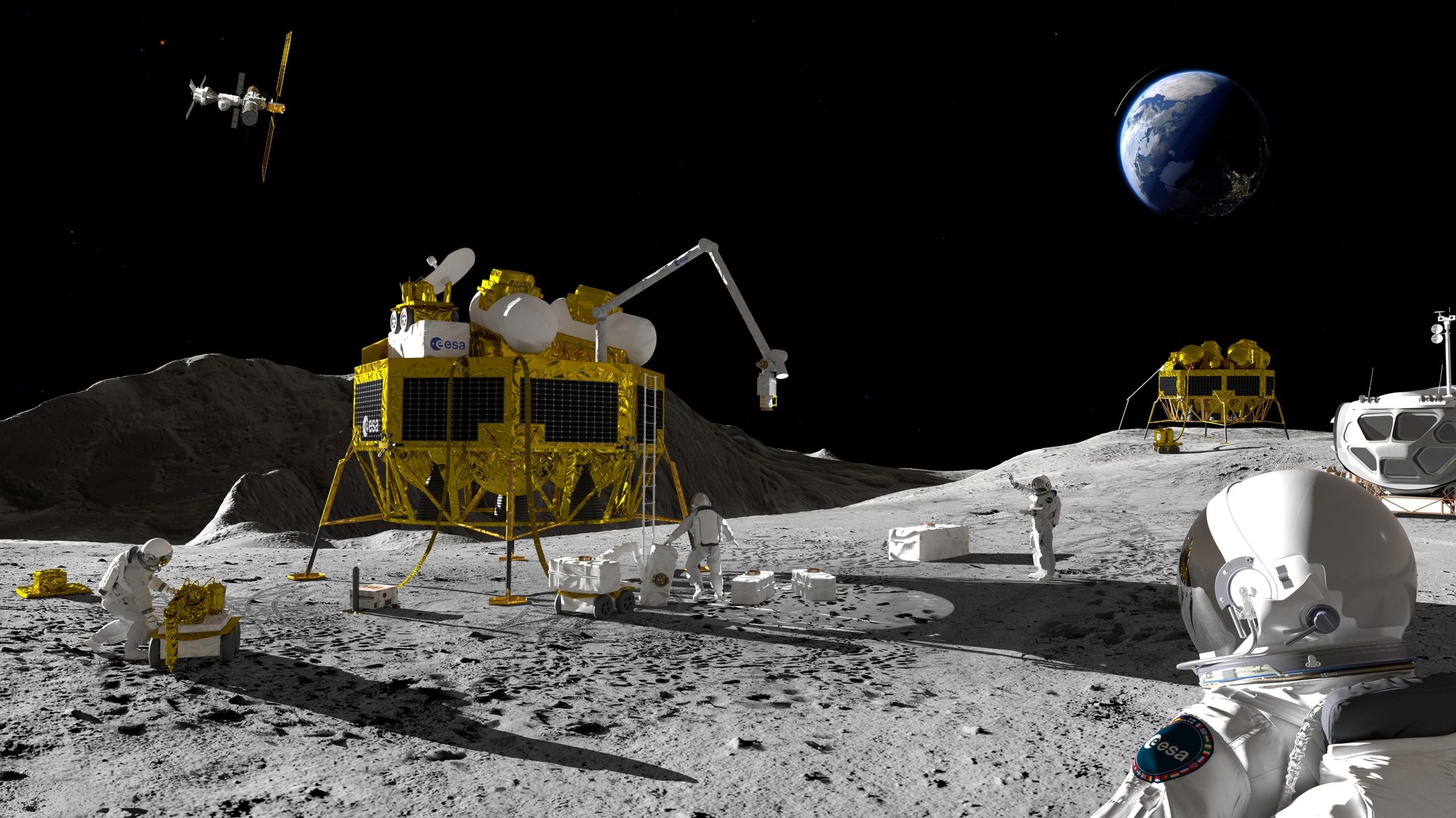

Künstlerische Darstellung des Monderkundungsszenarios. Bildnachweis: ESA-ATG

Architektur für gemeinsame Monderkundung

„LunaNet ist ein Rahmen aus gemeinsam vereinbarten Standards, Protokollen und Schnittstellenanforderungen, der es zukünftigen Mondmissionen ermöglicht, zusammenzuarbeiten, konzeptionell ähnlich dem, was wir auf der Erde für die gemeinsame Nutzung getan haben.“[{“ attribute=““>GPS and Galileo,” explains Javier Ventura-Traveset, ESA’s Moonlight Navigation Manager, coordinating ESA contributions to LunaNet. “Now, in the lunar context, we have the opportunity to agree on our interoperability approach from the very beginning, before the systems are actually implemented.”

Timing is a crucial element, adds ESA navigation system engineer Pietro Giordano: “During this meeting at ESTEC, we agreed on the importance and urgency of defining a common lunar reference time, which is internationally accepted and towards which all lunar systems and users may refer to. A joint international effort is now being launched towards achieving this.”

On the 20th day of the Artemis I mission, Orion captures the Moon during its lunar flyby. The image was taken by a camera mounted on the European Service Module solar array wings, on December 5, 2022. Credit: NASA

Up until now, each new mission to the Moon is operated on its own timescale exported from Earth, with deep space antennas used to keep onboard chronometers synchronized with terrestrial time at the same time as they facilitate two-way communications. This way of working will not be sustainable however in the coming lunar environment.

Once complete, the Gateway station will be open to astronaut stays, resupplied through regular NASA Artemis launches, progressing to a human return to the lunar surface, culminating in a crewed base near the lunar south pole. Meanwhile, numerous uncrewed missions will also be in place – each Artemis mission alone will release numerous lunar CubeSats – and ESA will be putting down its Argonaut European Large Logistics Lander.

Artist’s impression of the lunar Gateway, a habitat, refueling, and research center for astronauts exploring our Moon as part of the Artemis program. Credit: NASA/Alberto Bertolin

These missions will not only be on or around the Moon at the same time, but they will often be interacting as well – potentially relaying communications for one another, performing joint observations or carrying out rendezvous operations.

Moonlight satellites on the way

“Looking ahead to lunar exploration of the future, ESA is developing through its Moonlight program a lunar communications and navigation service,” explains Wael-El Daly, system engineer for Moonlight. “This will allow missions to maintain links to and from Earth, and guide them on their way around the moon and on the surface, allowing them to focus on their core tasks. But also, Moonlight will need a shared common timescale in order to get missions linked up and to facilitate position fixes.”

ESA’s Moonlight initiative involves expanding satnav coverage and communication links to the Moon. The first stage involves demonstrating the use of current satnav signals around the Moon. This will be achieved with the Lunar Pathfinder satellite in 2024. The main challenge will be overcoming the limited geometry of satnav signals all coming from the same part of the sky, along with the low signal power. To overcome that limitation, the second stage, the core of the Moonlight system, will see dedicated lunar navigation satellites and lunar surface beacons providing additional ranging sources and extended coverage. Credit: ESA-K Oldenburg

And Moonlight will be joined in lunar orbit by an equivalent service sponsored by NASA – the Lunar Communications Relay and Navigation System. To maximize interoperability these two systems should employ the same timescale, along with the many other crewed and uncrewed missions they will support.

Fixing time to fix position

Jörg Hahn, ESA’s chief Galileo engineer and also advising on lunar time aspects comments: “Interoperability of time and geodetic reference frames has been successfully achieved here on Earth for Global Navigation Satellite Systems; all of today’s smartphones are able to make use of existing GNSS to compute a user position down to a meter or even decimeter level.

Picture of the far side of the Moon taken on flight day six of the Artemis I mission from the Orion spacecraft optical navigation camera. Credit: NASA

“The experience of this success can be re-used for the technical long-term lunar systems to come, even though stable timekeeping on the Moon will throw up its own unique challenges – such as taking into account the fact that time passes at a different rate there due to the Moon’s specific gravity and velocity effects.”

Setting global time

Accurate navigation demands rigorous timekeeping. This is because a satnav receiver determines its location by converting the times that multiple satellite signals take to reach it into measures of distance – multiplying time by the speed of light.

Your satnav receiver needs a minimum of four satellites in the sky, their onboard clocks synchronized and orbital positions monitored by global ground segments. It picks up signals from each satellite, which each incorporate a precise time stamp.

By calculating the length of time it takes for each signal to reach your receiver, the receiver builds up a three-dimensional picture of your position – longitude, latitude, and altitude – relative to the satellites. Future receivers will be able to track Galileo satellites in addition to US and Russian navigation satellites, providing meter-scale positioning accuracy almost anywhere on or even off Earth: satnav is also heavily used by satellites.

Credit: ESA

All the terrestrial satellite navigation systems, such as Europe’s Galileo or the United States’ GPS, run on their own distinct timing systems, but these possess fixed offsets relative to each other down to a few billionths of a second, and also to the UTC Universal Coordinated Time global standard.

The replacement for Greenwich Mean Time, UTC is part of all our daily lives: it is the timing used for Internet, banking, and aviation standards as well as precise scientific experiments, maintained by the Paris-based Bureau International de Poids et Mesures (BIPM).

Galileo is based on a worldwide time reference called Galileo System Time (GST), the standard for Europe’s satellite navigation system, kept close to UTC with an accuracy of 28 billionths of a second. Accurate timings enable accurate ranging for position and navigation services, and their dissemination is an important service in its own right. Credit: ESA

The BIPM computes UTC based on inputs from collections of atomic clocks maintained by institutions around the world, including ESA’s ESTEC technical center in Noordwijk, the Netherlands, and the ESOC mission control center in Darmstadt, Germany.

Designing lunar chronology

Among the current topics under debate is whether a single organization should similarly be responsible for setting and maintaining lunar time. And also, whether lunar time should be set on an independent basis on the Moon or kept synchronized with Earth.

A mosaic of the south pole of our Moon showing locations of major craters, with images taken by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. Credit: NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University

The international team working on the subject will face considerable technical issues. For example, clocks on the Moon run faster than their terrestrial equivalents – gaining around 56 microseconds or millionths of a second per day. Their exact rate depends on their position on the Moon, ticking differently on the lunar surface than from orbit.

“Of course, the agreed time system will also have to be practical for astronauts,” explains Bernhard Hufenbach, a member of the Moonlight Management Team from ESA’s Directorate of Human and Robotic Exploration. “This will be quite a challenge on a planetary surface where in the equatorial region each day is 29.5 days long, including freezing fortnight-long lunar nights, with the whole of Earth just a small blue circle in the dark sky. But having established a working time system for the Moon, we can go on to do the same for other planetary destinations.”

Um richtig zusammenzuarbeiten, muss sich die internationale Gemeinschaft schließlich auch mit einem gemeinsamen „zentralen Referenzrahmen“ zufrieden geben, ähnlich der Rolle, die auf der Erde der Internationale terrestrische Referenzrahmen spielt, der die konsistente Messung präziser Entfernungen zwischen Punkten ermöglicht unser Planet. Entsprechend zugeordnete Referenzrahmen sind wesentliche Bestandteile heutiger GNSS-Systeme.

„In der gesamten Menschheitsgeschichte war die Exploration tatsächlich ein wichtiger Treiber für die Verbesserung der geodätischen Zeitmessung und von Referenzmodellen“, fügt Javier hinzu. „Es ist definitiv eine aufregende Zeit, dies jetzt für den Mond zu tun und auf die Definition eines international vereinbarten Zeitplans und einer gemeinsamen Zentralisierungsreferenz hinzuarbeiten, die nicht nur die Interoperabilität zwischen den verschiedenen Mondnavigationssystemen gewährleisten, sondern auch eine große Anzahl von Forschungsarbeiten vorantreiben wird und Anwendungsmöglichkeiten im Mondraum.“

„Gamer. Unglückliche Twitter-Lehrer. Zombie-Pioniere. Internet-Fans. Hardcore-Denker.“

More Stories

Identische Dinosaurier-Fußabdrücke auf zwei Kontinenten entdeckt

Der Perseverance-Rover der NASA beginnt einen steilen Aufstieg zum Rand eines Vulkankraters auf dem Mars

Der Generalinspekteur der NASA veröffentlicht einen vernichtenden Bericht über Verzögerungen beim Start des SLS-Raumschiffprojekts